Origins of chess

From Chesspedia, the Free Chess Encyclopedia.

The origins of chess is one of the most controversial areas of board gaming history. Countries which, at one time or the other, have been associated with invention of chess include China, India, Egypt, Greece, Assyria, Persia, Arabia, Ireland and Uzbekistan.

By far, the most commonly held belief is that chess originated in India. The earliest mention of chess appears in the Indian classic, the Mahabharata, written circa 2,000 BC, where it was called Chaturanga. As a matter of fact, the Arabic, Persian, Greek and Spanish words for chess, are all derived from the Sanskrit Chaturanga. The present version of chess played throughout the world is ultimately based on a version of Chaturanga that was played in India around the 6th century AD. It is also believed that the Persians may have created a more modern version of the game after the Indians. In fact, the oldest known chess pieces have been found in excavations of ancient Persian territories.

Another theory exists that chess arose from the similar game of Chinese chess, or at least a predecessor, thereof, existing in China since the 2nd century B.C. Joseph Needham and David H. Li are two of many scholars who have favored this theory.

Contents |

Origins of chess pieces

Chess-like pieces

Ever since the earliest times, and especially with regards to the most ancient of preliterate societies, chess-like pieces - isolated from whatever boards they could have been played on - were only simple figurines cut from stone, or made from clay and fired, and for their small size could have been used to help in accounting in trade and commerce. As some researchers have come to believe, some tokens represented goods or merchandise in transit; including them in a caravan made the trading trip that much more legitimate, and may have invested in them a degree of talismanic luck. Trading partners relied upon the tokens as representatives of the real thing - a cube could represent a crate, a tiny horse figure could represent a horse, and a pod on a stalk could represent a bushel of grain. Insofar as ancient commerce goes, this sort of thing has immense practicality when it comes to balancing one's ledgers, and indicating whether partial shipments are meant to be completed with future shipments. No less important is the matter of exacting tribute from a subject people, and keeping track of how much tribute has been arrived at. This becomes all the more important in an economic network having no common currency, and where debts are satisfied with payments in kind. (In the Near East, for instance, clay tokens have been found in archaeological digs, and some believe that is how man's earliest writing systems first began - from pressing these tokens and figures into clay or waxen tablets, and eventually shipping the tablets instead of the tokens, as an accurate statement of accounts is the easiest way to avoid ill feelings between distant trading centers. It is widely assumed that the cuneiform system of writing on wax or clay tablets followed very shortly after the practice of passing along the tokens.) But anyone who has had to deal with the drudgery of accounting knows that the tabulation and manipulation of tables of tokens is anything but fun, and ought to admit that that is a far cry from a game.

Chess pieces as talismans

An argument can also be advanced that chess pieces hewn from stone were miniature versions of totems, useful for representing and predicting the conflict of divine forces in nature or society according to scientific methods available to anyone curious enough to inquire. As did many other ancient people, the Ancient Romans kept little wood statues - lares et penates - by them in their houses and at work for good luck and good health, and considered spiritual power to be present in them, and emanate from them, wherever they were put. They were not merely placed on pedestals to repose there for general purpose veneration, they were brought and placed where they were believed to have the greatest effect - at the dinner table, the library, the bedroom, the business office, or the garden. Not all talismans were figurine in shape; many were cut or carved or minted in the shape of coins - some with magic words inscribed on them - and attached to chains for use as pendants; of course, attaching them to chains must render them less accessible to play on a chessboard. Regardless, the chess pieces of the game Shogi may have found their origin in a line of development similar to that. Even still, it is one thing to throw such pieces on a square grid, in a manner reminiscent to divination, as in the I Ching, counting perfect throws against those where pieces straddle dividing lines, and it is quite another thing altogether to have them start from fixed positions and wage war against each other.

Chess pieces as objects of art

In any case, it was not until mankind had advanced thus far in art and technology that little stone figures could be placed on a rectangular grid, and used for some kind of game pieces, whether as animals or men, or wagons or ships, or towers and castles, that chess came close to being invented. In fact, as artisans became more proficient in the manufacture of porcelain, glass, and brick, and were able to make castings in metal, noble families too poor to obtain and maintain private zoos for themselves could still amass beautiful collections of figurines of animals, highly suitable for games when not otherwise reserved for private viewing. (A man on a horse - the knight of chess - was, for example, one of the most common figures in puppet shows in the Middle Ages, and making a puppet was far more complex and elaborate than is the case today, with many of them often having porcelain heads connected to segmented bodies and limbs capable of independent movement, including ability to mount and dismount from the steeds that they rode.) The existence of sets of miniature figures could well have made the invention of chesslike games inevitable, and a mere matter of time.

Further development of chess

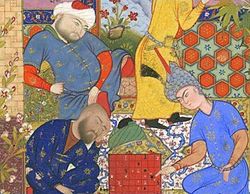

Chess eventually spread westward to Europe and eastward as far as Japan, spawning variants as it went. From India it migrated to Persia, where its terminology was translated into Persian, and its name changed to chatrang. The names of its pieces were translated into Persian along the way. Although the existing evidence is weak, it is commonly speculated that chess entered Persia during the reign of Khusraw I Nûshîrwân (531-578 CE).

From Persia it entered the Islamic world, where the names of its pieces largely remained in their Persian forms in early Islamic times. Its name became shatranj, which continued in Spanish as ajedrez and in Greek as zatrikion, but in most of Europe was replaced by versions of the Persian word shāh = "king".

Among other early literary evidence for chess is a middle-Persian epic Karnamak-i-Artakhshatr-i-Papakan which mentions its hero as being skilled at chess. This work is dated with some reserve, however, at 600 CE: The work could have been composed as early as 260 CE and as late as 1000 CE. The earliest evidence which we can date with some certainty is in early Arabic chess literature dating from the early 9th century CE.

The game spread throughout the Islamic world after the Muslim conquest of Persia. Chess eventually reached Russia via Mongolia, where it was played at the beginning of the 7th century. It was introduced into Spain by the Moors in the 10th century, and described in a famous 13th century manuscript covering chess, backgammon, and dice named the Libro de los juegos.

Chess with dice from romane epoch was found in France with Charlemagne figure sculpted on king pieces, and backgammon game.

Other theories

Many of the early works on chess gave a legendary history of the invention of chess, often associating it with Nard (a game of the Tables variety like Backgammon). However, only limited credence can be given to these. Even as early as the tenth century Zakaria Yahya commented on the chess myths, "It is said to have been played by Aristotle, by Yafet Ibn Nuh (Japhet son of Noah), by Sam ben Nuh (Shem), by Solomon for the loss of his son, and even by Adam when he grieved for Abel." In one case the invention of chess was attributed to Moses (by the rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra 1130 CE). However, this claim is strongly opposed by Muslims, since Chess is considered by some to be forbidden in Islam.

India

- Cox-Forbes theory - that chess originated from the four-handed chaturanga which was called Chaturaji.

- Shahnama theory - that chess was a replacement for war.

China

Literary sources indicate Xiàngqí may have been played as early as the 2nd century BC (see chess in early literature). Other battle-like board games played in antiquity without dice include the ancient Chinese game of Go, still popular even today. Although the origins of Go may extend as far back as 2300 BC [1], substantial supporting evidence dates no earlier than the 3rd century BC. The oldest surviving remnant of ancient Chinese Liubo (or Liu po) dates to circa 1500 BC. Nevertheless, Liubo, though sometimes considered a battle game, was played with dice. According to a hypothesis by David H. Li, general Han Xin drew on Liubo to develop the earliest form of chess in the winter of 204 BC-203 BC.

Iran

The Karnamak-i Ardeshir-i Papakan, an epical treatise about the founder of Sassanid dynasty, mentions the game of chatrang as one of the accomplishments of the legendary hero. It has a proving force that a game under this name was popular in the period of redaction of the text, supposedly the end of the 6th century or the beginning of the 7th. Closely related is a shorter poem from about the same period entitled in Pahlavi Chatrang-Nâmag, dated around AD 600, dealing with the introduction of chess in Iran.

The oldest clearly recognizable chessmen have been excavated in ancient Afrasiab, today's Samarkand, in Iranian domains contrasts with the absence of such items in India. Afrasiab was under the Islamic rule since 712, but were essential an Iranian cultural domain of Persian origin.

As Bidev, the Russian chess historian pointed out, nobody could possibly generate the rules of chess only by studying the array position at the beginning of a game. On the other hand, such an achievement might be made by looking at backgammon (in Persian Takht-I Nard), which is another Iranian game-invention.

Egypt

There is evidence of two ancient Egyptian battle-like board games played without dice. Particularly, Plato attributes Egypt as the origin of petteia, played in the 5th to 4th centuries BC, but nothing more is known about the game (see reference page 261 at Greek Board Games). Another such ancient Egyptian game was seega (idem, pp. 270-271).

Greece/Rome

Yet another game described by Plato is the ancient Greek battle game poleis, a "fight between two cities" (see pp. 263-265 at Greek Board Games). Varro (Marcus Terentius) is credited with having documented our earliest record (1st century BC) of the Roman battle game, latrunculi (idem, p. 259), commonly confused with ludus latrunculorum (mentioned below). Varro's original reference, posted in Latin, appears at Varro: Lingua Latina X, II, par. 20.

When chess reached Germany, accidental coincidence of the imported word schach = "chess" and "check" with the old native German word schach = "robbery" led some people when writing in Latin to use the names latrunculi and ludus latrunculorum to mean "chess".

Ireland

The main claim for Irish origin is the claim that two chess tables were bequeathed in the will of Cathair Mor who died in 153 CE. The Celtic game of fidchell is believed to be a battle game, like chess (as opposed to a hunt game, like tafl or brandub), and possibly a descendant of the Roman game ludus latrunculorum. However, these games were completely unlike chess.

See also

- A History of Chess, a history by Harold James Ruthven Murray published in 1913.

- Timeline of chess

External links

- The history of chess on Anatoly Karpov Homepage

- Chess, Iranian or Indian Invention? by Shapour Suren-Pahlav

- On the origin of chess by different authors

- Origin and Evolution of chess by Alex Kraaijeveld

- A Brief History of Chess by Paul Payack

- The history and origin of chess by Imran Ghory

- The Origin of Chess by Sam Sloan

- The History of Xiangqi

- The Origin of Chess